Between Collection and Allegory – Łukasz Ronduda Curator Łukasz Ronduda traces the theme of ‘collecting’ through the artists’ recent projects, and gives an account of the development of Enthusiasts project

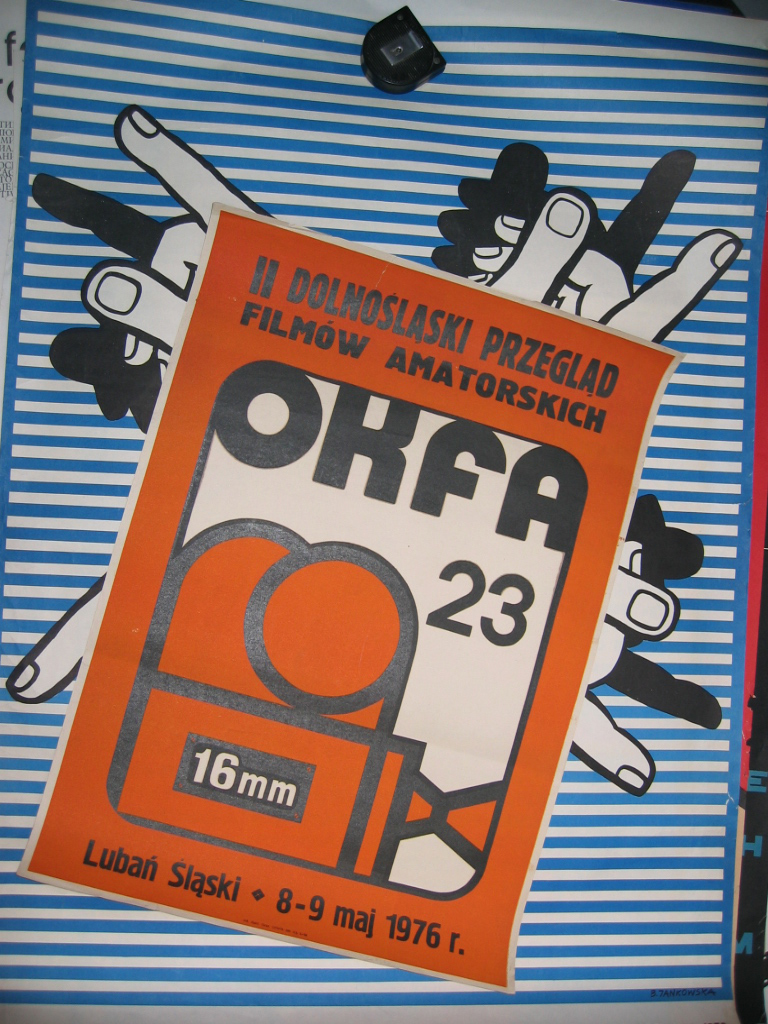

In their project Enthusiasts, Marysia Lewandowska and Neil Cummings summarize almost two years research into the “ruins” and remains of the amateur filmmaking movement that flourished in Poland from the early 1950’s to the end of the 1970’s.The artists present a singular “compilation” of items, mainly films, amassed during a collection-driven, allegorical search. I have to emphasize that Lewandowska and Cummings have striven to disrupt the collector’s passion – aimed at preserving the value, meaning and history of an object or phenomenon – with an allegorist’s desire to inject their own ideas into the object.Although counter to the dominant post-modernist strategies of allegorization, Lewandowska and Cummings have avoided “assassinating” their object of analysis through reducing it to a mere metaphor for endless additional signification.Instead, their treatment of the films they have gathered shares much with Benjamin’s understanding of allegory as a means of rescuing the past by “establishing a second level of meaning,” they have sought to create conditions for restoring public awareness in previously forgotten material.

This approach has resulted in a project shaped by a specific tension between two main levels of meaning. At the level of Collection, their endeavor is both sociological and artistic. It consists of the desire to re-present films made by amateurs between the 1950’s and 1970’s, and to turn attention to the work of a socially and historically marginalized group. At the level of Allegory, on the other hand, in reading a phenomenon that interests them and arranging the collected materials, the artists have produced a highly relevant critique of contemporary material culture. Enthusiasts is thus an extension of Lewandowska and Cummings’ previous interests, evident in such works as Free Trade; which explored the entanglement of art and emerging capitalism in Manchester, or Capital, an examination of the relationship between the Bank of England and London’s Tate Modern, as repositories of financial and symbolic capital. In Enthusiasts the artists investigate aspects of symbolic production (amateur film) that existed in a planned socialist economy. Based on the logic of “differences,” they examine contemporary culture as shaped by the free market, through revealing its dialectical opposite.

Allegory

Lewandowska and Cummings understand contemporary artistic practice to be a process that involves a complex exchange of references, between the art world and the wider social contexts through which art is produced and engaged. This context largely determines the cultural value of an artwork, for value results from the interaction of factors that include marketing, art history, fashion, the prestige of institutions that exhibit or acquire the work, art criticism and sources of financing. From this perspective, a work’s cultural value seems to derive from a “game of differences” between competing forces and opposing views, which remain dispersed, in constant exchange, and dependent upon each other. By adopting a multi-disciplinary position, Lewandowska and Cummings are able to articulate these disparate processes.

In their new project, they apply this approach to symbolic products that were developed in a micro context, i.e. the social network that was the amateur film movement in socialist Poland. The project is an expedition in search of values that have been lost in commercial film production, and largely absent from a professionally structured contemporary visual culture.

In many cases, the productions of amateur filmmakers were expressions of “basic” creative needs or genuine artistic ambition in environments rarely conducive, to this kind of activity. But they were also something else – something not burdened by “artistry” and unrelated to contemporary art. Lewandowska and Cummings like the idea of a “film proletariat” joining in the means of symbolic production – through cameras and film stock – by exploring their immediate surroundings; projecting their bold dreams and intimate desires. The artists are fascinated by the emergence of ambitious individuals who organized themselves into Amateur Film Clubs in order to create films about their own realities; a “grassroots” energy that redefines relations between culture and everyday practice. In The Esthetics of Resistance, Peter Weiss accurately describes this desire for cultural participation through the example of the cultural self-education of Berlin’s workers in 1937: “Our understanding of culture very rarely correlated with what appeared as a colossal reservoir of goods, accumulated inventions and discoveries. Stripped of ownership, we approached this amassed wealth at once frightened and pious, until we realized that we needed to fill all this with our own evaluations, that the general concept would become useful only once it said something about our living conditions and the difficulties and peculiarities of our thinking” (Weiss, 1995).

The core of the Enthusiasts project at the Centre for Contemporary Art is a selection of films which the artists have divided into three themes: Love, Longing and Labour. The first two consist of films representing the longings and desires of amateurs. The last is a collection of films picturing the conditions of production, i.e. the real contexts within which the filmmakers worked, lived and created. This tension between Labour and the two remaining themes– between the public and the individual – defines the exhibition’s dynamic. By juxtaposing films made by people caught within industrial production and images “produced” by amateurs, the artists hint at the shift that occurred “from a system of machine-based production, to the individual, to the production of individuality.” The filmmakers evoke a relatively successful micro-modernization of public life in which “the world as experienced individually proved capable of creating institutions limiting the inner logic of economic and administrative systems” (Habermas, Warszawa, 1996).

In presenting this image of the micro-community of amateur filmmakers, the artists focus our attention on the mechanisms that contributed to its creation. Enthusiasm, self-organization and self-awareness are among the principle “motors” that co-create culture and enable existence within the public sphere of signs. These are also guarantors of the healthy functioning of this sphere. Lewandowska and Cummings acknowledge these values as “essential” and independent of any political system. By evoking them within their own project, the artists question the phantasmatic tendencies of contemporary visual culture. The theme of Labour, which shows the progressive fetishization in socialist culture of images of industrial labour, might also be read as a critique of our current fascination with images of products. For the projection is a kind of inversion of contemporary consumer culture, which fetishizes finished goods while concealing the “real” conditions under which they are made. In comparing these two myths – one of socialist culture, the other of capitalist – the artists seem to articulate the fundamental dilemma of the post-socialist countries: “How do we escape these dual ghosts – the ghost of the historical past and the ghosts that are born with accelerated capitalist modernization” (Žižek, 2001).

Collection

For the artists, the gathering of amateur films in the exhibition is a “basis for allegorical reflection,” though it might also be considered independently. Against the background of this collection as a whole, certain genres are made more visible: the erotic cinema of Franciszek Dzida and Piotr Majdrowicz for example, could be characterized as a pioneering “aesthetic awareness” that resisted the normalizing efforts of the community; the “cinema of observation” of Henryk Urbańczyk and Jerzy Ridan; Leszek Boguszewski’s reflexive cinema; the satirical films of Jan Piechura and Antoni Sieńkowski; the animations of Marian Koim and Krzysztof Szafraniec; Tadeusz Wudzki’s and Leon Wojtala’s films about workers, to name but a few. Lewandowska and Cummings’ selection reveals that Poland’s amateur film heritage consists above all of vast resources of highly valuable symbolic capital. This heritage is multi-dimensional and varied in terms of genre – a fact paradoxically made evident by such problematic discoveries as amateur pornographic films from the 1970s.

Projecting these films -perhaps unavoidably- evokes feelings of nostalgia, and melancholy. The artists strive to “disarm” this feeling by stirring up additional allegorical meanings, meanings that reveal “the surprising currency of what seems to have irretrievably passed but can return in spite of the flow of history” (Benjamin, 1996). For the intention is to “enliven history, make it a motor of life itself, transform the antiquary weight of history into bodies capable of participating in creating the present” (Benjamin, 1996). The artists treat history as a reservoir of unused opportunities and potential paths of development that have thus far gone unfulfilled. And so, they counter a chronological vision of history with one that is fragmentary, closer in its intention to an archive or collection; for they see history as a collection of many narratives, some more visible and remembered, some less. By seeking out and creating a new context for the “story” of Polish amateur filmmakers of the 50’s-80’s, Lewandowska and Cummings seem to enact Alan Sekula’s directive: ”The archive has to be read from below, from a position of solidarity with those displaced, deformed, silenced, or made invisible by the machineries of profit and progress” (Sekula, 1989). We should remember, in the context of this project, that archival film material shown today inevitably becomes an allegory of history and of the passage of time, which is irretrievable in and of itself. It remains the same in its critical relation to the present. In The Culture of Amnesia Huyssen wrote, “The reconstruction of memory in the face of the currently ruling amnesia is an attempt at shattering the «eternal now» of the contemporary «culture of simulation». As a form of «radical experience of time», memory is a means by which the avant-garde can constructively involve itself in cultural history, reviving its own aspirations towards social change” (Huyssen, 1999).

With their “performative archive,” Lewandowska and Cummings challenge the dominant way in which archival film material is often treated by the contemporary entertainment industries of television and cinema (as well as the traditional artistic treatment of found footage), which entails fragmenting the material, stripping it of historical context, and reducing it to “film footnotes.”

The artists present the films they have unearthed in their entirety, treating them as testimony of a period in history characterized by very specific economic, social and cultural conditions. They assemble them into sets and series, but their aim is not motivated by formal concerns, but above all the organization of knowledge, the desire to conduct an allegorical discourse. In light of this, Lewandowska and Cummings’ activities can be interpreted as a manifestation of a specific artistic tradition described by Benjamin Buchloh in the Anomic Archive (Buchloh, 1999). In this text, Buchloh attempts to differentiate a series of artistic projects (for example, the Atlases of Richter and Warburg) that arose at the fringes of science and art, and are difficult to distinguish from “instructional boards, technical and scientific visualizations.”

Apart from presenting amateur films in curated “themes”, the exhibition also includes a fictional “reconstruction” of a typical club room from the 1970’s as well as a projection of excerpts from official Polish newsreels. Thus, in some way it resembles an ethnographic or historic display. This combination of including the works of amateur filmmakers in their own exhibition and “borrowing” from the languages of other disciplines enables the artists to play with the identity and exhibitionary habits of an institution like the Centre for Contemporary Art.

The projection of Polish newsreels is also important because it allows the artists to contrast “visualizations” of life in socialist Poland produced by amateurs with official, professionally constructed film history. As Andre Malraux contended, “it is impossible to separate our understanding of the history of the 20th century from its photographic and filmed representations.” It is for this reason that archival films are treated as proof or as a “visual fact” that supports the objectivity of a given historical account. By juxtaposing these two projections (i.e. two different “filmed” histories of Poland, two different archives), the artists effectively initiate a discussion about filmed representations of the past, their influence on how we experience the past, and even evoke the issue of the ownership of images that define the past. The film archives relating to the years 1945-1989 in Poland are currently managed according to a corporate logic, instead of being open and publicly available. It is almost impossible to gain access to the films from this period for research or artistic purposes. The artists touch upon this issue in the final element of their installation, namely, a film archive that provides viewers the opportunity to watch on DVD any film from the material collected, that they choose. Ultimately, in pursuing the creation of this archive of Polish amateur film, the artists emphasize the importance of democratizing this realm of imagery that defines the past and constitutes “public history,” and simultaneously to warn against its privatization.

Lewandowska and Cummings’ installation manifests, in the spheres of collection and allegory, a sensitivity to issues of the “defense of the public realm” against subordination to the laws of the market, a sensitivity to the issue of the hidden processes of memory in the socio-cultural subconscious. The project expresses highly ethical standards employed by the artists, who have attempted, like “born-again modernists,” to overcome the post-modern drive of privatization of languages by directing our sensus communis onto a path of non-consumer reflection.

Bibliography:

Peter Weiss, The Esthetics of Resistance, [in:] Jürgen Habermas, Modernizm – niedokończony project, [in:] Postmodernizm, (ed.) Ryszard Nycz , Kraków 1996.

Slavoy Žižek, Przeklenstwo fantazji, Wrocław, 2001.

Allan Sekula, Reading an Archive, [in:] Blasted Allegories: An Anthology of Writings by Contemporary Artists, (ed.) Brian Wallis, Cambridge 1989.

Andreas Huyssen, Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia, New York 1995.

Benjamin Buchloh, Gerhard Richter’s Atlas: The Anomic Archive, October 88, Spring 1999.

Walter Benjamin, Anioł historii selected and edited by Hubert Orłowski, Poznań, 1996.