Enthusiasts Speaking – Marysia Lewandowska A series of interviews conducted by Marysia Lewandowska with Film Club members, who talk about club life and their fim-making experiences

Part 1

A hot summer day. Industrial premises surrounded by a blue wire fence. An ivory coloured polish fiat appears in an empty car park. A freestanding sign, also blue, with plain white letters: THE CHYBIE SUGAR FACTORY. An old redbrick building. On the second floor, a suite of rooms. Behind the first door, a former darkroom, full of obsolete equipment and storage for canned film reels. Two remaining rooms; a meeting room with armchairs and a film editing table, and a make-shift cinema with a projection booth.

Four big, swivel armchairs placed around a low 80’s table. A tall middle-aged man with thinning fair hair standing, preparing a ‘Turkish’ coffee. He places a box of sugar cubes from the factory on the table.

Franciszek Dzida, AKF “Klaps”: –The circumstances weren’t conducive to setting up a film club. The majority of local people either worked on a farm or in the sugar factory. We had two music groups – one chamber ensemble and one rock band – that were fairly active at the time.

– Where did the idea of a film club come from?

He asks this question of himself. Looking through the window, he’s silent for a while.

– I have to go back to the 50’s, to my personal history. Since I was a child my father would take me to the cinema. His love for cinema started before the war. He was running a painting and decorating business but in his free time he turned to painting pictures. This was his real interest.

– Fine art has always been close to my heart but I also felt an urge to tell stories. I began making films, which are a combination of art, story-telling and music. I was fascinated by how a film image emerges, how a trail of light creates something moving on the screen, on that white canvas. It all happened in the local cinema, in Chybie, which unfortunately closed down a long time ago.

– From that moment all my decisions have lead towards film. I gave my soul to film. Nothing, not even political changes could drag me away from film, or from my desire to realise my ambition through film.

Kazimierz Pudełko, a strongly built man, enters the room. He carries a bag of cold beers and offers them around, served in tall glasses with the inscription “Żywiec”.

Franciszek Dzida: – I’ve been ‘touched’ by the magic of cinema. When my military service in Szczecin finished and I qualified as a cinema operator, I obtained access to a projector and films. I used to screen more ambitious films than those from a typical cinema repertoire, more of a DKF (Discussion Film Club) type. I felt a need to talk about films, and to analyse them. I started looking for other contributors. I was employed as a technician in the sugar factory; around me there were metal-workers and electricians. I proposed setting up a film club in the factory. This was to become our window onto the world, to allow us to break away from our provincial vision and this small town mentality. At the time, I felt a great affinity with Bergman. It was only that he was able to work with different film stock and different budget. But other than that, we were both part of the same film community, we shared the same passion for film. I needed it immensely, not because I felt oppressed by the system; everyone could find a way around that!

Loud laughter.

– It was a chance to mark our presence. Being an artist was one way of marking that presence. It felt like a great honour. Today everybody is an artist, so you have to look really hard to find true artists.

Kazimierz Pudelko, AKF “Klaps”:– The first camera we bought was funded by our colleague Józek Orawiec. We took it with us on a trip to the Pieniny Mountains. After that, a chairman of the Central Council of Trade Unions at the factory decided to look after us. We began to buy more equipment, and to meet every Tuesday and Friday in a tiny room in which the films were made and discussed. Then we started to participate in festivals, screenings, and so on.

– The film Thistles by Jan and Franek Dzida was my début as an actor; I played the main character. My own film Smooth Skin was not quite finished yet. Some of our material was sent to Bydgoszcz to be developed, and we would have to wait about a month before getting it back. Occasionally, it was poorly developed, so we had to re-shoot some more.

Franek continues his story. His hands rest on the arms of the chair.

Franciszek Dzida:– When my colleagues joined the “Klaps” club, it changed them enormously. Cinema transformed them. One by one, they left the sugar factory, got more qualifications and began to study. Our greatest achievement was this incredible transformation. We all eventually succeeded in entering the cultural sphere and getting noticed by the press.

Franek gets up from the chair, walks to the bookshelf and takes down a big brown album full of press cuttings, old photographs, certificates, letters and souvenirs.

– We felt like different people, exactly as it was shown by Kieślowski in that famous final scene of Camera Buff when Filip turns the camera towards himself. He changes as a person when the camera starts to record ‘his own life’ instead of being simply a toy.

– Every Tuesday for the last thirty-five years we have been presenting world cinema here, from classic movies to the most recent releases. We tape them from television, or rent them. In the beginning, we were showing films by Bergman, Fellini, Antonioni, Tarkovsky, all avant-garde directors. Things like Men in Black had no screenings here. Now we screen Jarmusch, Almodovar, von Trier. We recently realised that we used hand-held cameras in a similar way to Dogma, back in 1972.

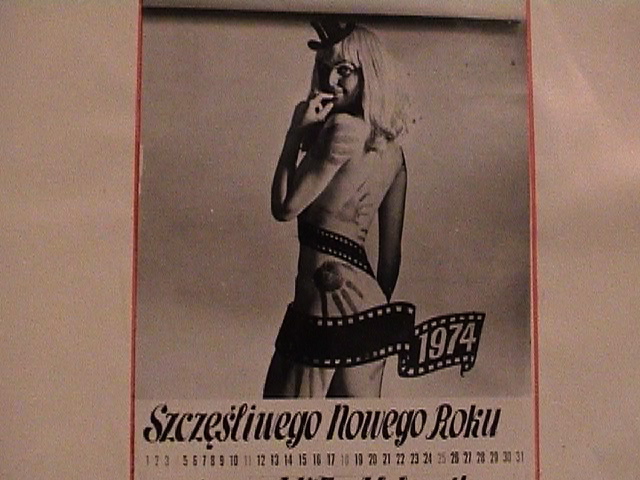

A noisy truck roars past outside, drowning Franek’s words. He gets up and shuts the window. A calendar with a naked pin-up reflects in the glass-pane. He continues talking.

– During martial law when everything was closed we continued to function normally. We were showing some censored stuff, including Bugajski’s films; as you know in Poland everything can be arranged. We were never involved in politics. I don’t like art that accommodates a political opinion of one kind or another. At times there were 40 of us in the club and we never discussed politics. Maybe that helped us to survive all the systems. One of the most politically dramatic moments was in 1976 when the authorities wanted to close the club down. They tried to close it a few times. The club had already been active for 7 years and I had never been a party member. One day I was asked to attend the executive party meeting. The then local secretary said to me:

“Neither the content nor the form of these films correspond with the cultural policy of a socialist factory.”

– That is how he presented his side of the argument. It was a very serious ideological accusation. Since I was prepared for everything, I asked him…

“So how come our films win prizes for their outstanding educational value?”

– At that time we had already won many trophies and prizes. Of course, these prizes were not given for Mayday parade films, we never sent these to competitions or festivals. It was back in the 70’s and our films were touching on urgent problems of the time. We showed young, disillusioned people, just like it is today. Our films explored issues such as alcoholism, yobbish behaviour or gang rape, as in our film The Parable.

-Then he adds …

“You think we are all so stupid here?”

-And I turned to him to say…

“You, Mr Engineer, are an expert on sugar, perhaps sugar refinery, but you are not an expert on film. You don’t know what means we employ in our films, what narration is, how the storyboards are planned, how editing is done, or how the sound is synchronised.”

This started a big row and even the first secretary intervened. We had already been making films for almost eight years and had good contacts with the press and radio. Everybody was keen to visit us because everything here was just the way it was, without any pretence. Finally, I won that battle but decided to leave the factory. It was such an ideologically draining fight on quite a unique scale. I always felt they had their reasons and I had mine.

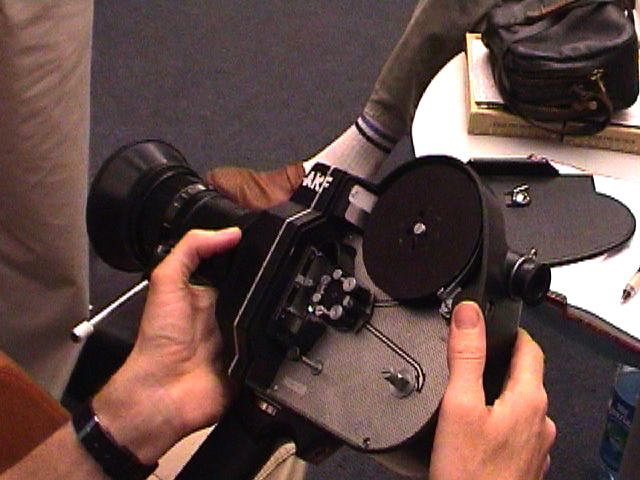

Kazimierz brings a Krasnogorsk camera into the room, puts it on the table next to the albums.

Franciszek Dzida:– Amongst the films we made at that time, parades were extremely significant. Money was always available for these kinds of official ceremonies. When we were asked to record a local Mayday parade, we would write a preliminary shooting schedule, and list our requirements, for example: 10 reels of film of such and such sensitivity, 10 colour reels, etc.

– In the beginning we had three cameras and shot film with all three. But for those in charge at the factory, the only thing that mattered was that ‘something’ was recorded. Because it raised the status of the event, as did the presence of the cameramen. It was very different to now, when everyone keeps a DV cam in the cupboard next to a bowl of sugar.

– In fact, we were also happy… because we didn’t have to take part in parades. There was no obligation for us to carry banners, or “Lenin” placards. Everybody hated it. By the way, the whole of Poland detested it, because you always had to simulate, or pretend something. We felt free from all this. Being a reporter or a journalist had a special aura. But soon I realised that nobody wanted to watch our Mayday films. I tried to organise screenings several times, inviting party officials, but nobody came.

– So in the following years we ordered 20, 30 reels, and ‘loaded’ only one camera, the others were ‘running’ empty with only the springs wound up. The cameras could be heard humming zh-zh-zh-zh-zh-zh-zh. An experienced cameraman can tell the difference when a spring is just wound, without film, the sound it produces is completely different.

– My colleagues were filming the parades with empty cameras, and almost all the film stock we saved for our own films. So thanks to the Mayday parades, artistic cinema emerged. We were cheating, because nobody controlled us, because nobody was interested. With time the image of the parades also acquired a patina, got more refined. It now represents a record of when all those people were young. Now their children and grandchildren hire those films, we made them available in our local video store. They say, “Look, here our grandma walks with a banner, and uncle carries a ‘Lenin’ ”. It’s just nostalgia, it’s not tinged by any political agenda, any aversion or hatred of the system. And only a pure cinema remains.

In the next room there are several rows of beige fake-leather upholstered armchairs. Franek turns on a video player. The first film is screened and a hand-painted title appears “Somewhere in Poland” 1969.

Franciszek Dzida:– We were never that interested in slogans, we were interested in spectacle. One of our first films was about a church fair in Chybie. I can still vividly remember a mechanic at one of those factory meetings when our films were noticed for the first time. It was in 1971 and he accused us……….

“So this is what a film club is for, to show Catholic celebrations… but our country is secular.”

– We wanted to show that a church fair is full of junk. There was a vast array of toys – on one side there was a naked Brigitte Bardot doll and on the other a Madonna figurine. There was no big ideology attached to the film. We were just fascinated by the contrasts. We were becoming increasingly sensitive to personal concerns and engagements, we wanted to preserve those; it was about us.

New scenes appear on the screen: a group of young people fooling around during a trip to the woods, a picnic on the grass, a close-up of kissing lovers.

– Eroticism was a forbidden and ridiculed subject because it was perceived from a specific Polish perspective at the time. We filmed love… there was nothing scandalous or demoralising about it. I have been fighting with this Polish philistinism for years. All our films from the 70’s onwards contained rather brave erotic elements. Living in this provincial town you had to be either a stuntman or madman to expose yourself like that.

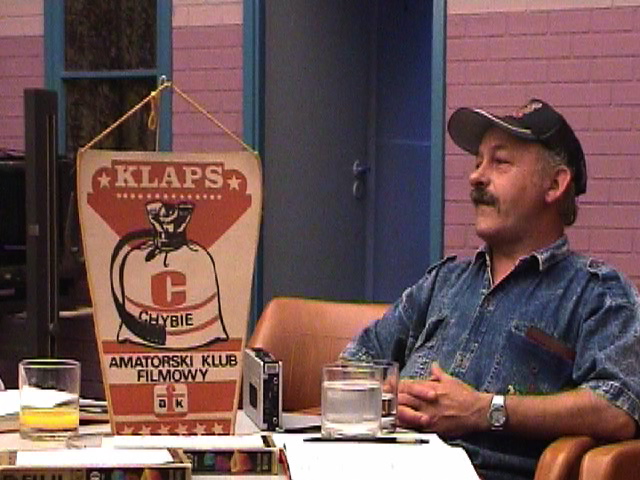

A short man with a moustache, Józef Orawiec, enters the room. He wears a denim shirt and black baseball cap. He shakes hands with everybody, takes a small tape recorder out of his bag and puts it on the table next to the “Klaps” film club’s pennant. He switches it on. Franek continues talking.

Franciszek Dzida:– I would like to emphasise that this place, this club, thanks to celluloid film, was a place where another world ruled… it was a magical place. People who used to attend our meetings realised they were entering another reality, the ‘real world’ as created by us. It’s where our love for feature films originated from, less so for documentaries as they didn’t capture the full drama. This was a safe place that above all allowed us to become more conscious. You stopped being a metal worker or an electrician and became an artist. Regardless of your skills, you were an artist in a sense of your identity. Here you wanted to express something; and here you had something to say.

– To make a film is to create a world of fiction, an imaginary world. I still don’t like the reality out there and in my own mind another world exists. It only partly receives signals from the other reality. We all live in a particular moment, in this system, in this country. Our imagination feeds on what surrounds us, what we are familiar with. We cannot draw from some cosmic reality. I don’t like science fiction because it appears false.

Reel with footage from the world premiere of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s “Camera Buff” at AKF Klaps, Chybie, 29 Sept 1979

Franek looks for a VHS tape shot at the premiere of Kieślowski’s AMATOR (Camera Buff )in Chybie. He points at the framed photographs on the walls. The cinema-like room has been painted pink. On the screen there is a long shot of the workers filling up the seats at the factory hall.

– From 1969 to 1975 we organised film presentations every year. From ‘75 we organised nine nation-wide film festivals and the last one was in 1993. Ten years before that we started running film workshops to which lecturers, and directors from Warsaw were invited. Piotr Łazarkiewicz and Stanisław Niedbalski, a documentary cameraman came first, followed by people from Gdańsk, and Wrocław who started making films about this little village. In 1988, some Danes came and filmed hours of material on Chybie. They recorded many interviews, with a doctor, local government officials, the manager of the sugar factory and others, later they edited it together into a portrait of our place.

Józef Orawiec, AKF “Klaps”: – The happiest moment was when Kieślowski visited our club. When he left the screening and sat next to me at the bar, we started exchanging ideas. I talked about my diptych The Feast and he mentionedDecalogue for the first time. It was a short moment, perhaps it lasted five minutes, and then Franek shouted “Mr film director! Welcome!”.

Franciszek Dzida: – To say we have always been fond of cinema, is putting it mildly. Cinema has been our whole life.

End of part 1

Part 2

Gdańsk-Orłowo railway station in the evening. A dark subway. A metallic blue Mercedes from the 70’s waits in the street. A pleasant looking man welcomes two visitors. Snow is falling thickly.

A villa from the 50’s. A creaking wooden staircase leads to a landing. Big modern paintings are hanging on the walls. The owner of the house is a painter. An ‘artistic’ mess everywhere. A desk with a laptop and piles of paper, an atmosphere of interrupted work.

A bell rings. An older man dressed in a winter anorak and ski pullover enters the room. Julian Jaskólski from“X Muza” AKF, Gdańsk; brings a DVD with his films. He slides it into the laptop. He talks about filming of “The Toy Soldiers” in 1962, based on the screenplay and directed by Ryszard Wawrynowicz in collaboration with Józef Rodziewicz.

Julian Jaskólski AKF “X Muza”:– It was at the time when anti-war movies were being made. Something was happening in Cuba. We were making films to express that a human being is worth more than those toys, commanders or other people interested only in waging wars.

– As producer and cameraman, I was responsible for The Toy Soldiers film. LOK, The National Defence League, lent us the guns, a broadcasting station and equipment to set up a battle-field. All the film was developed in drums, in a very DIY way. The original print got lost somewhere. What we see here is reconstructed from rushes. We spent a month shooting on the Łeba dunes.

-In this film it doesn’t matter who represents what nationality and who fights against whom. The actors, Leszczyński and Kreja, are both dead now. Kreja was a railwayman, working on the Warsaw-Gdynia Express route. Leszczyński made several films. His film Let the Earth Restwas awarded the Grand Prix in Gdansk. Wawrynowicz left for the States and nobody has heard about him since.

The image is temporarily ‘frozen’ through a glitch in the computer. It shows single frames, suspending the action of the film.

– In 1963, in the Nation-wide Festival of Amateur Films at the Żak club in Gdańsk we received a Grand Prix. Each year the Festival was organised at a different city in Poland. Later our films entered competitions further away, at UNICA (Union Internationale du Cinema non Professionnel) festivals in Salerno, Dubrownik.

A local night shop. A saleswomen washing the floor; no customer in sight. The sound of clanging beer bottles in a carrier bag, it’s a late winter evening.

Julian’s flat. The front door is protected by a metal grill. We enter a small neat room-cum-studio, with equipment for video editing, and a TV set. A little table, two chairs, intimate lighting.

– I would like to mention another film made in 1970, The Heart, it’s about the Batory ocean liner. We learned by chance that this ship was to stop operating. In those days it connected the Polish community living in the USA with the old country and we felt quite sentimental about it. The Batory‘s final hour came, and the ship was moored in Kościuszko Square, to be used as a hotel. It couldn’t stay there for much longer since the maintenance was becoming far too expensive. There were rumours that the ship was to be sold so we decided to make a film about it. Later, we learned that the ship was destined for Hong Kong, to be recycled into razor blades. We intuitively made the film before the December riots in Gdańsk, bearing in mind that the next amateur film festival that was planned to take place on the Batory itself. However, it was cancelled and moved to the hotel Miramar in Sopot.

Julian takes out the club’s commemorative albums, puts them under the lamp on the table, he comments on each page out of over a hundred.

Katowice. A 60’s housing estate. White and orange high-rise blocks of flats, surrounded by shrubs, Birch trees and lawns covered with grey snow. Somebody is walking a dog. An early winter afternoon.

The flat of Jan and Danuta Macków, former members of “Śląsk” Amateur Film Club. The furniture is from the 60’s when they first moved in. Ład designed armchairs and a sofa, other pieces of furniture inherited from their grandparents. One of the walls of their grown up daughter’s bedroom is covered with photographic wallpaper showing a Swiss alpine landscape in autumn. The couple are sitting on the bed against that background.

Jan, an older handsome man with a lively face and a grey goatee wears a black-and-red check shirt. His wife Danuta, is an elegant woman with neatly trimmed fair hair, good-natured, dressed in a blouse with irregular geometrical patterns.

Jan Maćkow: – Our enthusiasm was not only part of our character, but due to the very situation in which we found ourselves. The second world war has just ended and everybody wanted to relax, enjoy time with friends, have fun, go dancing and talk. Most of us were longing for the youth we hadn’t really experienced because of the war and we wanted to make up for it. Somehow we just got together, people of different professions, educational backgrounds and ages, but all of us wanted to be teenagers once again. In the beginning our club revolved mostly around parties and gatherings. We spent every New Year’s Eve together. We organised fancy dress balls, three-day trips to the Beskidy Mountains. I remember Janusz Kidawa walking to the border with a bottle of vodka to have a drink with the Czech guards.

– The first club members were: Poloczek, Boronowski, the Rydzewskis, the Sójkas, the Kokocińskis, the Fischers, Szatan, Koniora, Gerlotka, Badura, Breguła, Rzepkiewicz, the Cholasas, Forbert, Cywiński, the Idziaks, parents of the well known cameraman Sławomir Idziak, around twenty people all together.

Danuta walks out to the hallway to look for the Idziak’s phone number in the directory.

-We were one of the first amateur film clubs to exist in Poland, so we soon noticed the effects of our work. We started winning competitions and prizes, which was rather encouraging.

– In the beginning we put up our own money, so no sponsor could place demands upon us. We initially worked using pre-war equipment. However, one day our instructors, Poloczek and Boronowski, came to the conclusion that the authorities should be informed about our activity. I was part of the delegation that went to a meeting in the Regional Workers Party Committee in Katowice. We paid a visit to the Propaganda Department where we gave a fancy speech. We said how hard the life of working class people was, suggesting that a film club would provide them with a space to ‘breathe’, how the level of culture would improve if some important local events were recorded. During that time a branch of the Polish Film Newsreel (PKF) hadn’t been established in Katowice yet. They bought our ‘tales’ and led us to a shelter in the basement under the Committee building. There they had stored German 16 mm cameras and films from the 40’s. We were given two spring-winding Movikon cameras with an extra Zeiss lens that was used for filming from airplanes. It was dream-like equipment.

Danuta sits closer to her husband so that she can fit in the frame.

Danuta Maćkow:– When ‘television arrived’, a lot changed at the club. It was the end of the 50’s, for us the Przemysław’s Year represented a turning point. The more inspiring social bonds started to loosen up. Some people from “Śląsk” got involved professionally with film and no longer had much time to participate in the club’s programme.

– My husband and I worked together, although I concentrated more on research. We made the film Przemysławtogether, but I spent more time in the library and ended up making most of the props. For each film the film crew was made up of club members doing the lighting, sound, camera, direction, assistants, etc.

The sharp sound of a car alarm pierces the window from the parking lot below.

Jan Maćkow: – We were among the youngest members of the club. Others already had jobs and came to the club to pursue their non-professional interests, mainly connected with photography. I was keen on drawing but I was not into film yet. In 1951 I started a job to pay back the scholarship I had received from the Foreign Trade Central Office in Katowice. We used to sit in an office, with not much to do because it was the era known for an excess in employment; everybody wanted to be on as many payrolls as possible. I quickly realized that office work was rather boring so I began to look for something else which would allow me to blow off steam, a way of spending my free time. After finishing work I would have whole afternoons to myself. I got to know about the Photographic Society through my friends. Some people there were very advanced in photography but in the beginning this didn’t grab me. I only got into the swing of things when it turned out that we would be able to realize our own film ideas. Our first instructors were Edward Poloczek and Norbert Boronowski, whose experience dated back to pre-war years. They really encouraged our enthusiasm. I started to attend meetings regularly, studied theory in detail and started to make notes, plans and drawings for films while I was sitting in the office.

Danuta Maćkow: – Thinking now about the role of women, you could say that they were bringing ideas down to earth, doing research for scripts, taking part in filming and writing notes. Their role was mainly to inspire and to tone down. They acted as the very first and the sharpest of critics. Every woman wanted her husband to become successful in the club.

Danuta goes to the kitchen to fetch a plate of cream cakes.

Jan Maćkow:– As amateurs, our films talked about what was happening around us. Films that explored controversial subjects or talked about various situations critically, even in a veiled way, were very rare in those early days.

Jan calls for a taxi. A silver Toyota arrives. It’s the evening rush hour. The central railway station fills up, as a muffled female voice announces the next train.

End of part 2

Part 3

Poznań. A clear, sunny winter’s day, white smoke from a distant factory chimneys billows on the horizon. A deserted city centre. Sunday morning. A neo-Romanesque castle; austere interior, typical 30’s marble floor, wooden panelling, crystal chandeliers. In one of the hallways, an exhibition of the members of a local art club, a café next to it and a room which claims to be Hitler’s study. In the west wing, a door with a small plastic sign: AKF “Awa”, The Castle Cultural Centre, Poznań.

A typical club room, a low table, shabby armchairs, a shelf with trophies, a statuette resembling an Oscar, a notice board with pinned photographs documenting visits of Kieślowski, Karabasz, Zagroba. Old posters fill the walls.

A young man mounts a digital camera on a tripod, turns on the spot light. A group of middle-aged men standing, chat. The eldest of the men sits down in one of the armchairs pushed against the club notice board. He starts telling his story about the beginnings of AKF “Radok” in Rawicz. Others listen, joining in turns.

Stefan Skrzypek, AKF “Radok”: –Around 1964 a group of local people used to get together in the cinema, not in the auditorium, but in the projection booth. We met the projectionist, a really old man who we called ‘grandpa’ who owned a cinema and made films before the war. The repertoire was excellent, the interest was huge, and therefore we used to come to his booth quite often and watch movies for free. In the late 50’s going to the cinema was really something special; it was difficult to get a ticket, it was quite expensive, and you could often only get them from a tout.

The Radok Club in Rawicz was affiliated to the Cultural Centre because of a rumour we received concerning a film camera deposited in a safe at the Presidium of the Regional National Council. It had been bought by the Presidium years ago but had never been used. We came to the conclusion that if we set up a club we could get access to it. And that’s exactly what happened.

– The first film we made was a Rawicz Film Newsreel, which was shown every three months in the local cinema before the main film. It was a special addition.

– I insisted on calling it a newsreel. We were filming during Maydays and the July 22nd celebrations. We would usually film a report that we were asked for but there was always a lot of 8mm footage left over. One day we started looking through it, and began editing it together. We made a separate film and called it “Celebrations’. It is a documentary about a Mayday parade but shown, so to speak, through the back door. There were shots that could never have been included in the official version. The film was simply made in conspiracy, while many years later it was presented on television. I can say this story is evidence of how each event can be shown and interpreted differently.

Janusz Piwowarski, AKF “Awa”:–The difference was that Polish Film Newsreel showed official Mayday celebrations from Warsaw, whereas Rawicz Newsreel showed them in Rawicz where people could see themselves. This seemed the biggest draw for people to the cinema.

Stefan Skrzypek:– I also want to mention another social aspect. Coming here I realized it’s a Sunday today. In those days on Sunday you had to get up very early and queue outside the newsagents’ to get the weekly colour magazines like Dookoła Świata,Przekrój, Film.They were not expensive, each was one zloty, so they were selling fast. You went home, read them and the next day passed them to somebody else so that a wide range of people had a chance to read them before the following Sunday.

– The year 1965 was truly spectacular. There was a UNICA [Union Internationale du Cinema non Professionnel] Congress in Marianske Lazny in Czechoslovakia. It was great because we were able to stay there for almost 2 weeks. This was the world congress with lots of different nationalities. The hall for 500 people was full. I remember the feeling when a French or Belgian movie was shown and blood on the screen was in colour. It felt incredible because at that time our films were only black and white. As soon as we returned home we started to shoot in colour. East German Orwo Color film stock became available, then we called it “Orwo Horror.”

A man in a light grey suit comes in. Jerzy Jernas apologises for being late. Pan Stefan continues.

– That trip was very inspiring. We decided to learn more about film in general, as we didn’t know much about it, not to mention actual film-making. We proceeded in two ways. We began by renting the prize-winning films to have a closer look at them, we even set up an Amateur Film Cinema and watched the films there. We were familiar with films, such as award winning Regi Poloniaeby Jan and Danuta Maćkow from AKF “Śląsk”, Dykteryjki i Ramotyby Karol Alchimowicz from “Jupiter” in Bydgoszcz. Romuald Zielazek from Poznań came here once a week to run a course in which a considerable group of people, not only club members, participated.

– We set up a small clubroom with tables, a projection room and a bar and eventually managed to buy some equipment. There was an agreement between the Cultural Centre and our Club regarding financial support, although our ambition was to generate our own income. We started organizing Filmmakers Balls which brought us a lot of money. After one ball we immediately purchased a new Pentaflex camera.

Piotr Majdrowicz, AKF “Awa”: – How did the Filmmakers’ Ball work?

Stefan Skrzypek: – We built a film set and issued numbered tickets. Around 300 people attended and we organised film screenings, which proved to be very popular. We also made films during the balls and made money by selling souvenir photographs taken during the ball. Subsequently the militia started harassing us, saying that our buffets contained all sorts of delicacies, like sausages and hams, whereas meat shops only offered empty hooks at the time.

Piotr Majdrowicz: – What was special about Rawicz was that you also organised poster exhibitions. At that time they were printed for each individual film, but unfortunately most have been lost.

Roman Madejski, AKF “Awa”: – In 1968 I was still at school and my father bought me my first movie camera, which I later paid back in instalments. In 1971 I joined the Palace of Culture in Poznań and the Film and Photography Studio where a group of people went to the cinema together, and had discussions… My need to make films emerged around this time. It was a way of expressing ourselves.

– In ‘71 we went to the Rawicz Amateur Film Presentations to learn how others were doing it and in ‘72 we started to take our own films. My Studio for Model Makingwas a commissioned film as we were expected to make at least one film for the Palace of Culture annually. My second film was an 8 mm movieHow to Have Fun. I made my last film in 1981 which means that I have spent 10 years in the “AWA” club, although I am still in touch with some of our colleagues.

– The most common subject matter was taken from our everyday surroundings, but in a very personal way. We all dreamt for our work to be seen by as many people as possible, and to hear their thoughts, not just praise, but an evaluation of its merits.

– Andrzej Jurga presented a TV programme on amateur cinema for a very short time. It was an important honour, and really encouraging, when one of our films was shown by him.

Mirosław Skrzypczak, AKF “Awa”: – At first it was not “Awa”, but the Studio of Film and Photography run by teachers from the Chemical School. The Studio occupied a basement under the tower of Poznań Castle. We had access to one Kwarc camera, one Pentaflex, and one Łucz. We experimented on 8 mm but all those films perished. I was a member from ‘67 to ’70 before I got a job in television and had no spare time to carry on with my own films.

A break. Several men stand in the doorway offering cigarettes to each other. Piotr goes into the storage-archive room and brings the commemorative album of the “Awa” club. He shows the page with a hand-written list of its first members. There are ten names on it. After the break the man in a light grey suit starts talking.

Jerzy Jernas, AKF “Awa”: – Janusz Piwowarski and I joined “AWA” when we were both 14. Our interest in film has affected our education. It widened our horizons and made us sensitive to what was happening around us. At that age your interests begin to be formulated and filmmaking filled our free time.

The clubs attached to factories were associated with people who often worked to a brief, although it didn’t apply to Chybie, where the strong personality of Dzida dominated. This was also the case with Wiepofama, where Ryszard Tomaszewski made commissions as well as his own films.

Janusz Piwowarski: – Through filmmaking and participation in the club events I learned to think and act more independently.

Jerzy Jernas:– It was important that we actually belonged to the club. Spending time there occupied a considerable part of our lives. It was our second home. We formed a strong community, talked about films and about life and hung out lot. We travelled to festivals together, went on holiday and went camping at the summer film festival in Łagów for many years. Strong emotional bonds still exist amongst the former club members.

– As with the majority of beginners, our attempts at making a feature film or semi-feature film were embarrassing. We had problems with sound and there was no dialogue. Perhaps this was beneficial because all those limitations forced us to think.

– The most common practice was to make an amateur film collectively, in cooperation with friends. Zinczuk and I were partners but the final decision was taken by one of us. If we had three minutes of film and a spring winding camera could hold only 30 seconds, it taught us a great discipline. If you have only three minutes to use, you have to think three or ten times about what to shoot. Video tape which costs almost nothing is a curse; you shoot a lot thinking it will be edited somehow later. But it’s not true, it never gets edited, and a lot of trash remains. Learning from the classics was a lesson of discipline.

The cameraman replaces the DV tape. Nobody pays any attention to it. They continue to listen.

– We weren’t forced to do anything, we only occasionally had to make a “congratulatory scroll” to celebrate the factory’s anniversary, something similar to a commercial nowadays. This was taken for granted and in no way interfered with the making of our own films. We didn’t identify with those commissioned jobs but at the same time we were aware that film can serve as propaganda. We wanted to talk about our own lives and our own worlds which didn’t resemble what was shown by the official city or factory newsreels.

The young man releases the camera from the tripod. He turns on the video player. Somebody draws the heavy curtains. We see shots from Rawicz on the monitor, a group of filmmakers with cameras get off the bus. The town welcomes amateur film makers with banners. It is 1971.

Poznań Central Station. A train for Warszawa Wschodnia arrives at platform one. An empty second class compartment with old PKP branded curtains trapped in the window. A man selling beer from a sports bag walks along the corridor. The train starts moving, at the very last minute he jumps out.

The script is based on interviews made in with amateur film-makers: Franciszek Dzida, Jan Dzida, Kazimierz Pudełko, Józef Orawiec from „Klaps” Amateur Film Club in Chybie; Stefan Skrzypek from „Radok” Amateur Film Club in Rawicz; Piotr Majdrowicz, Janusz Piwowarski, Roman Madejski, Jerzy Jernas, Mirosław Skrzypczak, Mikołaj Jazdon from „Awa” Amateur Film Club in Poznań; Jan and Danuta Maćkow from „Ślask” Amateur Film Club in Katowice; and Julian Jaskólski from „X Muza” Amateur Film Club in Gdańsk.