From Enthusiasm to the Creative Commons – Anthony Spira Interview with Neil Cummings and Marysia Lewandowska conducted by Whitechapel Gallery curator Anthony Spira

Anthony Spira

Apparently the root of the word amateur means one who has fallen in love and an enthusiast is one whom the ‘god’ has entered. How have you distinguished between amateurs and enthusiasts?

Neil Cummings & Marysia Lewandowska

We’re always nervous in the presence of god! “Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm,” said the very quotable Ralph Waldo Emerson.

AS

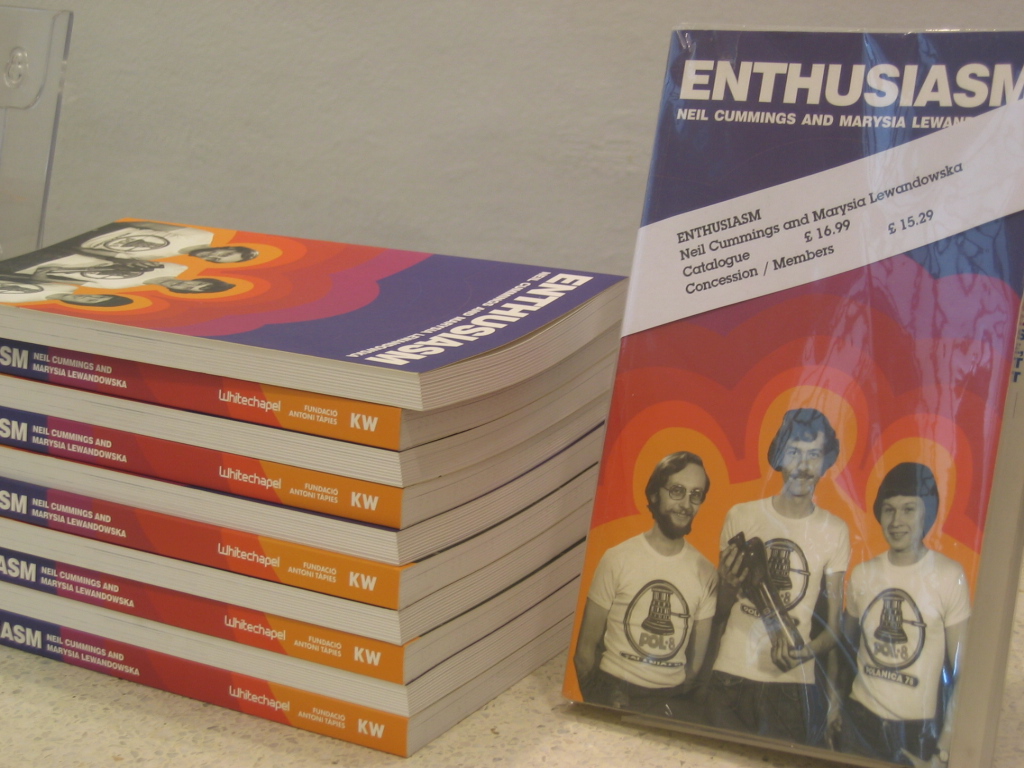

This publication, titled ‘Enthusiasm’, is the second volume produced in relation to your project with Polish amateur films from the Socialist era. Volume one accompanied the project’s first manifestation in Warsaw and was called ‘Enthusiasts’. Why did the title change to accompany the shows in London, Berlin and Barcelona?

NC&ML

The first exhibition looked particularly at the social and cultural context of the films and their makers – Enthusiasts. As we rethink and represent the films, the phenomenon of enthusiasm has become an important concept. Enthusiasm is the motivating force that enables all kinds of exchanges. We are using the films to trace a trajectory of enthusiasm, which seems to have been drained from the spaces of art, culture, free time, sport, and self-organization to become thoroughly instrumentalised; enthusiasm has replaced labour as a resource for contemporary capital.

AS

So your decision to examine the role of ‘enthusiasm’ in a contemporary context came through the activity of collecting and archiving forgotten films, films from a pivotal element of recent European history. This follows on from your previous projects, such as Not Hansard: the Common Wealth, 2000, where you collected printed material produced by local and national clubs, hobbyists, collectors and associations. And maybe Free Trade, 2003, too, where you traced the entanglements of art and capital through the Manchester Art Gallery’s collection. Could you describe your interest in archives and collections? You have previously said that an archival, documentary impulse in the west is motivated by self-promotion rather than self-preservation; it’s a way of writing one’s own subjectivity into the historical process.

NC&ML

Well, we’ve become interested in working with archives, as they seem to have an increasingly powerful grip upon culture, and its reproduction. There is an astonishing growth in digital databases of images and information, through data banks and image libraries. www.archive.org for instance regularly archives the whole publicly available www. It’s a gigantic data hoard that already dwarfs public libraries.

Public collections of art in museums and galleries store most (perhaps up to 80%) of their collection at any one time. And these collections (in Britain at least) can never let go of their accumulated material, they can never de-accession.

Archives, like collections are built with the property of multiple authors and previous owners. But unlike the collection, an archive designates a territory – and not a particular narrative. There is no imperative, within the logic of the archive, to display or interpret. And therefore the meanings of the things contained are ‘up-for-grabs’; it’s a discursive terrain. There’s a creative potential for things to be brought to the level of speech, as they are not already authored as someone’s (eg. a curator’s) narrative, or property. Interpretations are invited and not already determined, which is maybe why there is a creative space that many artists are responding too.

AS

What motivates you to make an exhibition out of an archive?

NC&ML

In the case of ‘Enthusiasts’, there was no pre-existing archive. It was distributed in people’s homes but had no public presence. There has been absolutely no interest from public institutions in the cultural production of the amateur or enthusiast unless it conforms to a notion of ‘folk art’ or craft. We had to track down former film club members by traveling all over Poland. The films were often stored in their houses and in some cases literally under their beds. We carried a portable 16mm film-viewer, so if we couldn’t screen the films we could at least glimpse them there and then. Once we had a sense of the range of material, we realised we would have to try and at least seed the idea of an archive.

It’s a long story but we found Łukasz Ronduda, curator at the CCA in Warsaw and set about trying to clean, restore and digitise as much material as we could find money or goodwill for. As the collection of films grew, we thought about an exhibition to start the process of interpretation and narration. In some ways we wanted to return the films to their audience. So we contacted the former state and film broadcasting archives in Poland as it occurred to us that it would be interesting to create an ‘official’ context into which the enthusiasts films could be placed. The archives are now charging extraordinary amounts of money for access, and even more for reproduction rights even in ‘educational’ contexts. Essentially, a large part of the cultural memory of a nation, which the state produced, is now denied to the very people who financed it. Similar archives exist throughout Britain too, like the North West Film Archive or internationally The International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) a collaborative association of the world’s leading film archives. It’s like charging for access to museums and libraries.

So we began to think about creating a ‘critical’ archive of amateur film, which in contrast to the former state archives, would – to use a term from software development – be ‘free’ or ‘open source’. This means that donated films will be digitised and made available online, not only to view, but to be used as a material resource for future filmmakers. We have been working with Alek Tarkowski, Justyna Hofmokl, Łukasz Ronduda and the filmmakers to enable the films to be licensed under versions of the Creative Commons licenses. The licenses are currently being translated, negotiations are underway and the beginnings of the Enthusiast Archive will be online soon. The Archive Lounge in the exhibition enables visitors to curate their own film programs. We hope it allows our selection of films under Love, Longing and Labour to be seen as partial, as one possible narrative strand amongst others and not in any way authorial or definitive.

We recently heard that the BBC are working on making much of their educational programmes available online. Thousands of hours of material will also be placed under the Creative Commons licenses as the Creative Archive.

AS

Your own website opens with the following words: ‘We recognise that it’s no longer helpful to pretend that artists originate the products they make, or more importantly, have control over the values and meanings attributed to their practice: interpretation has superseded intention.’ This explicitly explains your choice not to make objects but to treat the world as freely available ready-made material. This attitude is a feature employed by many artists today, even if less explicitly than you, just like a musician sampling and mixing existing tracks.

Could this equally be considered as a curatorial strategy? Perhaps the distinction between your practice and a curatorial one is the degree of intervention with the material that you use. Can you as ‘artists’ take more liberties with the material than a curator? In a sense, the context, environment, discussions, publicity – the whole system and presentation – becomes as important, if not more important, than the material displayed.

NC&ML

I think this is getting close to what we’ve talked about before as a feeling of responsibility or ownership of material for exhibition, interpretation or display; what you refer to as liberties. I guess for us there are only liberties. We are conscious that when you work with a ‘curator’ – and of course this is a generalisation – there is a pressure to act responsibly towards the artwork and the imagined intention of the maker or artist. There is an inbuilt deference. And I guess we feel little of that deference. Partly because much of the material we use already exists outside of the museum or art gallery in a wider ‘material culture’, it becomes art momentarily through our intervention, but can also dissolve back again into the realms of the ‘everyday’. And partly because we have been working with the technologies that enable objects and experiences to become artworks – museums and galleries, making exhibitions, producing publications and catalogues, writing wall and text-labels, and so on. When you work with these technologies you become aware that they can be turned upon any object, image, artist, maker, experience, city, country or nation. These important and powerful technologies are the means of interpretation, of producing the work of the work of art. This is where our recent work has resided, in taking liberties with the endless process of interpretation.

Once you turn attention away from the manufacture of artworks, to the technologies and institutions that designate the object as an artwork, then it’s right to say that the whole world opens-up as a ready-made. And with this in mind, the practice of artists – all artists, whether they acknowledge this or not – changes from that of struggling to originate, to struggling to choose. We choose from all the ideas, knowledge, objects, films and images that already exist; so the figure of the DJ sampling, or the curator or the hacker become much more appropriate metaphors.

In fact they are more than metaphors, they’re specifically chosen practices. Because if the idea of a ready-made is still vital, it’s in Duchamp’s gesture, a gesture which didn’t create a new object, but a new potential. He precisely exposed the conditions that enable the work of a work of art. He acted curatorially you might say.

AS

If all the codes of culture are freely available as materials and tools is it possible to distinguish between appropriation and exploitation?

NC&ML

There is a very, very fine line between appropriation and exploitation. And while we talked earlier about feeling little or no deference towards the art object, we take enormous care of social relationships when working with the cultural products of others. This often involves endless negotiation, explanation and collaboration so that everyone involved can see how the project develops and what our aspirations are, and they can decide whether to contribute (or not). Any responsibility resides in these personal exchanges between us and the people we are working with. Clearly, as artists –and again we’d suggest all artists do the same whether it’s acknowledged or not- we are able to capitalise on the creativity of others. The difference is that we acknowledge, make explicit and negotiate the terms under which it happens. We inevitably exploit, but would like to avoid exploitation.

AS

If people do not ‘own’ what they produce, does the idea of labour become redundant?

NC&ML

Very few people own what they produce. This used to be the privileged position held open for the idea of the artist, someone who was not alienated from the fruits of their labour. But this is clearly no longer the case. The ideal artist has become a model employee in deregulated economies reliant on self-motivation, enthusiasm, creativity, flexibility, and intuition. Labour, far from being redundant has merely changed its nature.

AS

What I meant to get at was that people are remunerated for their time (and effort). If the fruit of our time and effort becomes freely available, it loses any financial incentive. How are people supposed to earn a living if what they produce is not remunerated? Does intellectual property not have a similar value to physical property?

NC&ML

Financial incentives are not necessarily what drives enthusiasm. And maybe, this is something of a contradiction, but the fact that something is freely available does not necessarily mean that there are no financial incentives to produce it. There are an enormous cultural shift underway as we move –in Europe at least- to financial economies of immaterial labour; from the production of goods to the production of services, knowledge and information -like education, or creating exhibitions, or consultation. People often earn more than a living.

As for intellectual property, this seems one of the most keenly contested areas of cultural struggle at the moment across a range of otherwise disparate disciplines. And the simple answer is no. Unlike physical property where my ‘use’ of that good deprives others, or at least depletes the common pool of available resources – animal grazing rights is the example usually given. With ideas and knowledge this model is radically inverted. My ‘use’ of an idea does not necessarily stop other people using the idea. And it goes further, instead of ‘use’ depleting available resources, the more people using an idea the better it becomes. Sharing ideas and knowledge enriches, restricting their use does not.

By extending property relations to knowledge, we limit rather than enhance. If this applies to knowledge, then why should it not apply to digital goods and copyright? And then why not creativity, or genetic material, or language, or environmental resources?

One of the most interesting on-line developments is the growth in ‘free’ and ‘open source’ software, where the program is collaboratively developed, modified and redistributed –often based on gift economies, like blood banks or organ donation – by programmers and users. Some of the emerging applications, such as the Linux operating system, which is stable, cheap, virus free and under constant refinement by all its makers and users, is beginning to challenge the ‘market-dominance’ of commercial ‘restricted-source’ software, such as Windows. Peer-to-peer networks have re-animated generosity, and Wikipedia which is an on-line, ‘free content’ encyclopaedia is the fastest growing resource on the web currently expanding in 27 languages, peer reviewed and under constantly revision. All of these endeavors are sharpening interest in the public domain or the notions of the commons. Essentially they attempt to limit the power of copyright and patents to turn all creativity and knowledge into private property.

These models developed in the digital realm offer interesting ways for thinking about cultural activity, and even for practicing as artists.

AS

The limitless pool of material provided by the internet has accelerated shifts (not only for artists) from passive positions of voyeurism or spectatorship to ’empowered’ roles as editors, witnesses, judges. As we discussed earlier, instead of creating material in a vacuum, artists frequently perform as ‘facilitators’ or ‘conduits’ providing connections or constructing situations. Who do you see as pioneers of this way of working?

NC+ML

As for pioneers, the Situationists seem to be precursors (theoretically and practically) for much of what is happening at the moment, both on and off-line. And a whole range of (particularly American) artists and practices that emerged during the late 1980s were very influential for us, Artists who began to turn their attention to the structures through which art is produced, promoted, distributed and ‘consumed’. We’re thinking of artists like Julie Ault and Group Material, Andrea Fraser, Sylvia Kolbowski and a slightly older generation of Michael Asher and Hans Haacke: artwork that became tagged as ‘institutional critique’. We found this work both liberating and critical in that it enabled a model of ‘art’ and its circulation to be built and intervened in. At the same time we were conscious of how the notion of the ‘institution’ – and the museum is a great example – is devolving out into subtle social structures. The ‘exhibitionary’ function of Museums and Galleries merge into Public Relations, Education, Development and Sponsorship opportunities; networks of images, brands and knowledge that work upon emotional economies of loyalty, trust and enthusiasm. So here European artists have proved more supportive: Thomas Hirschhorn, Superflex, Tone O. Nielsen, Inventory, the Copenhagen Free University, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Matthew Higgs, Jeremy Deller, to name but a few, have been very, very influential on us.

The role of sociology and anthropology has been key for us too, the work of Michel de Certeau on the practice of everyday life, Pierre Bourdieu and his attempt to develop a methodology for representing cultural practices, and Tony Bennett describing the ‘exhibitionary’ complex. There have also been a couple of manifestos published recently which are also very inspiring. The Libre Society take models from ‘free’ software culture and see if they can be applied to other cultural and creative practices while ‘the hackers manifesto’ by McKenzie Wark, reformats a political economy derived from Karl Marx for our new networked times.

And yet for all the opportunities opened by collaborative models of cultural production there is still a tendency – and artists are their own worst enemies in this respect- to play down the amount of sharing, influence, collaboration and plagiarism that constantly goes on. These more collaborative models, evident in the film enthusiasts and resurfacing in the digital realm, offer interesting ways for thinking about cultural activity and practicing as artists.